The 2024 Indian elections have concluded. Indian voters have cast their votes and chosen the new government. With a landmark 969 million eligible voters, and 18 million first-time voters, and more than 2,600 political parties, election event of the world’s largest democracy grabbed all the possible headlines in the country and worldwide. However, in the midst of this festival of democracy between these dramatic democratic events, a supposed ‘gold rush’ has failed to live up to the fear psychosis that it engendered.

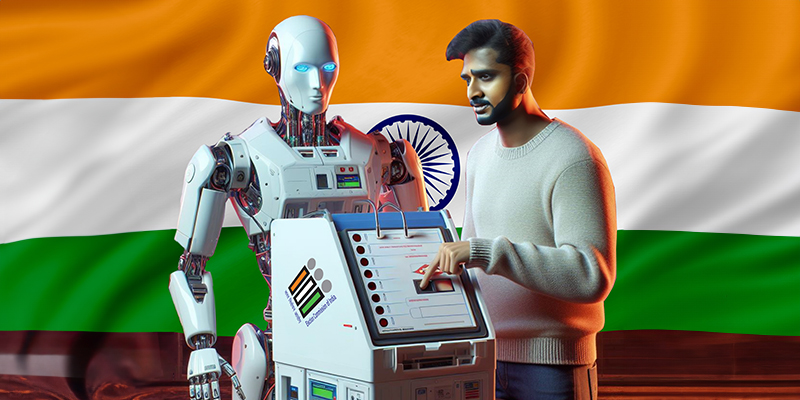

AI and its impact on the elections was one of the concerns this election season. However, in the finale, it has only been a sloppy technological intervention with teasers here and there.

2024 is the year of elections with more than half the world’s population casting its votes. While AI has the potential to enhance voter accessibility, the speculation was rife with high probability of cases of misinformation and bias. A whopping $50 million is estimated to have been spent by political parties in India this season on commissioning AI-generated election campaign material.

But the question remains- how did AI impact elections? And, more broadly, did AI impact democracy?

With a halo of uncertainty, the new entrant, AI walked away with the spotlight while voice cloning, deep-fake images of political leaders, old videos regenerated to today’s context, started to percolate- influencing the voters. To enable its movement, a hyper-equipped communications industry lent its infrastructure via social media, messaging apps and other digital channels.

The content created during this time was highly charged, fomenting the election emotions in hyper-local languages and sent to voters’ phones via whatsapp and other social media channels; most of these, unregulated and functioning like echo-chambers.

While the AI hype was infectious, its premature deployment caused a frisson among technological and democratic enthusiasts. AI-generated pictures, videos, and other human language systems started to cause curiosity, hatred, and fear. Any unregulated intervention seemed like looking for a needle in a haystack.

From the re-elected Prime Minister Narendra Modi, to the political leader such as Rahul Gandhi, AI-influenced content soon started to circulate freely on different fora. Archived doctored videos of departed politicians– J Jayalalithaa and M. Karunanidhi, the former Chief Ministers of the southern state of Tamil Nadu resurfaced, to try to influence voters.

Cut to 2024, most of the newsrooms delving and churning out news, set up desks to verify news, sources, data confirming a piece of information using tools such as Google reverse image search and Google lens, InVid, Google Maps/ Yandex, Fact Check Explorer for visual verification. For mapping geo-location tools such as yandex, google street view and google maps made it to the frontline. AI tools such as Itisaar were used for deepfake detection. Fact-checking units too got onto the bandwagon to address this gap.

In May, the Election Commission of India formulated a directive after a doctored video of Home Minister Amit Shah started to make the rounds. The directive stressed upon ethical and responsible use of social media, alerting against the spread of misinformation and deepfakes. On the use of AI, it said,

“The Election Commission of India has a constitutional duty to conduct free and fair elections and to ensure level playing field among the stakeholders. Accordingly, taking cognizance of the directions of the Hon’ble Delhi High Court in Writ Petition (C) (PIL) No. 6186 of 2024 and possibility of disturbing the level playing field by the Political Parties, their representatives and star campaigners by using “deep fakes”,

AI generated distorted content which spread fake information/misinformation/disinformation and distortions of facts, the ECI brings to the specific notice of political parties of the provisions of the Model Code of Conduct, the Information Technology Act, 2000 and the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code ) Rules 2021 , the Indian Penal Code and framework of the twin acts namely the Representation of People Act, 1950 and 1951 that govern the regulatory framework and underline the emphasis for the same.

It further added the regulatory framework provisions of Model Code of Conduct and related instructions to elaborate on different sections of the IT Act.

In an absolutely parallel universe, however, a new study was released this week by research group Epoch AI projects. It said that tech companies will exhaust the supply of publicly available training data for AI language models by roughly the turn of the decade – sometime between 2026 and 2032. For a technology dependent on inputs from its users, AI systems like ChatGPT will soon reach monotony. The report calls this a “literal gold rush” that depletes finite natural resources.

The Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) of the Government of India even set up an AI advisory in March and asked platforms to seek “explicit permission” before deploying any “unreliable Artificial Intelligence model(s)/LLM/Generative AI, software(s) or algorithm(s)” for “users on the Indian Internet.” Stressing on the integrity of the electoral process, it asked the platforms to ensure the process is free from bias or discrimination. Union Minister of State for Skill Development & Entrepreneurship and Electronics & IT Shri Rajeev Chandrasekhar said,

“Safety and trust of our Digital Nagriks is our unwavering commitment and top priority for the Narendra Modi Government. Given the significant challenges posed by misinformation and deepfakes, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MEITY) has issued a second advisory within the last six months, calling upon online platforms to take decisive actions against the spread of deepfakes.”

In an ecosystem where speed and authenticity are at loggerheads, the conversation around ethics of news reporting appeared to face the litmus test. And, the Indian elections have set a precedent as early movers in directing guard rails around the deployment of AI and thus have worked as gatekeepers to preserve the sanctity of the elections .

AI and its impact on the elections was one of the concerns this election season. However, in the finale, it has only been a sloppy technological intervention with teasers here and there.

2024 is the year of elections with more than half the world’s population casting its votes. While AI has the potential to enhance voter accessibility, the speculation was rife with high probability of cases of misinformation and bias. A whopping $50 million is estimated to have been spent by political parties in India this season on commissioning AI-generated election campaign material.

But the question remains- how did AI impact elections? And, more broadly, did AI impact democracy?

The grand entry

Ever since the AI buzz word and the new technology took over the world, the role of synthetic media over elections has created an atmosphere of fear mongering over technology and its possible implications on democracy. In India, the ecosystem was already grappling with missing voter names, poll-booth rigging and a climate of excruciating heat; all of this spread across two months of voting.With a halo of uncertainty, the new entrant, AI walked away with the spotlight while voice cloning, deep-fake images of political leaders, old videos regenerated to today’s context, started to percolate- influencing the voters. To enable its movement, a hyper-equipped communications industry lent its infrastructure via social media, messaging apps and other digital channels.

The content created during this time was highly charged, fomenting the election emotions in hyper-local languages and sent to voters’ phones via whatsapp and other social media channels; most of these, unregulated and functioning like echo-chambers.

While the AI hype was infectious, its premature deployment caused a frisson among technological and democratic enthusiasts. AI-generated pictures, videos, and other human language systems started to cause curiosity, hatred, and fear. Any unregulated intervention seemed like looking for a needle in a haystack.

From the re-elected Prime Minister Narendra Modi, to the political leader such as Rahul Gandhi, AI-influenced content soon started to circulate freely on different fora. Archived doctored videos of departed politicians– J Jayalalithaa and M. Karunanidhi, the former Chief Ministers of the southern state of Tamil Nadu resurfaced, to try to influence voters.

Gatekeepers of misinformation

As a 90s’ kid, I remember how every version of computer virus was followed by the release of an anti-virus software. Saviour, we called it. The tacit understanding was that both emerged from the same source and was a usual commercial practice to perpetuate business. Though I have no proof to corroborate this, often the hyper-links, attachments or fringe elements that one accessed, led to compromising computer or cloud data, with questionable security systems. Most times such vulnerability also meant instilling fear, dominating the narrative of data protection.Cut to 2024, most of the newsrooms delving and churning out news, set up desks to verify news, sources, data confirming a piece of information using tools such as Google reverse image search and Google lens, InVid, Google Maps/ Yandex, Fact Check Explorer for visual verification. For mapping geo-location tools such as yandex, google street view and google maps made it to the frontline. AI tools such as Itisaar were used for deepfake detection. Fact-checking units too got onto the bandwagon to address this gap.

In May, the Election Commission of India formulated a directive after a doctored video of Home Minister Amit Shah started to make the rounds. The directive stressed upon ethical and responsible use of social media, alerting against the spread of misinformation and deepfakes. On the use of AI, it said,

“The Election Commission of India has a constitutional duty to conduct free and fair elections and to ensure level playing field among the stakeholders. Accordingly, taking cognizance of the directions of the Hon’ble Delhi High Court in Writ Petition (C) (PIL) No. 6186 of 2024 and possibility of disturbing the level playing field by the Political Parties, their representatives and star campaigners by using “deep fakes”,

AI generated distorted content which spread fake information/misinformation/disinformation and distortions of facts, the ECI brings to the specific notice of political parties of the provisions of the Model Code of Conduct, the Information Technology Act, 2000 and the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code ) Rules 2021 , the Indian Penal Code and framework of the twin acts namely the Representation of People Act, 1950 and 1951 that govern the regulatory framework and underline the emphasis for the same.

It further added the regulatory framework provisions of Model Code of Conduct and related instructions to elaborate on different sections of the IT Act.

In an absolutely parallel universe, however, a new study was released this week by research group Epoch AI projects. It said that tech companies will exhaust the supply of publicly available training data for AI language models by roughly the turn of the decade – sometime between 2026 and 2032. For a technology dependent on inputs from its users, AI systems like ChatGPT will soon reach monotony. The report calls this a “literal gold rush” that depletes finite natural resources.

India- pioneering the entry with innovation and regulation

In February 2024, leading up to the Indian general elections, the now newly crowned Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman released the interim budget with a heavy push for AI. The industry is expected to grow at a year-over-year CAGR of more than 30%, it said.The Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) of the Government of India even set up an AI advisory in March and asked platforms to seek “explicit permission” before deploying any “unreliable Artificial Intelligence model(s)/LLM/Generative AI, software(s) or algorithm(s)” for “users on the Indian Internet.” Stressing on the integrity of the electoral process, it asked the platforms to ensure the process is free from bias or discrimination. Union Minister of State for Skill Development & Entrepreneurship and Electronics & IT Shri Rajeev Chandrasekhar said,

“Safety and trust of our Digital Nagriks is our unwavering commitment and top priority for the Narendra Modi Government. Given the significant challenges posed by misinformation and deepfakes, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MEITY) has issued a second advisory within the last six months, calling upon online platforms to take decisive actions against the spread of deepfakes.”

In an ecosystem where speed and authenticity are at loggerheads, the conversation around ethics of news reporting appeared to face the litmus test. And, the Indian elections have set a precedent as early movers in directing guard rails around the deployment of AI and thus have worked as gatekeepers to preserve the sanctity of the elections .